Trump tariffs live updates: White House mulls options, Supreme Court appeal after trade court setback Yahoo

source

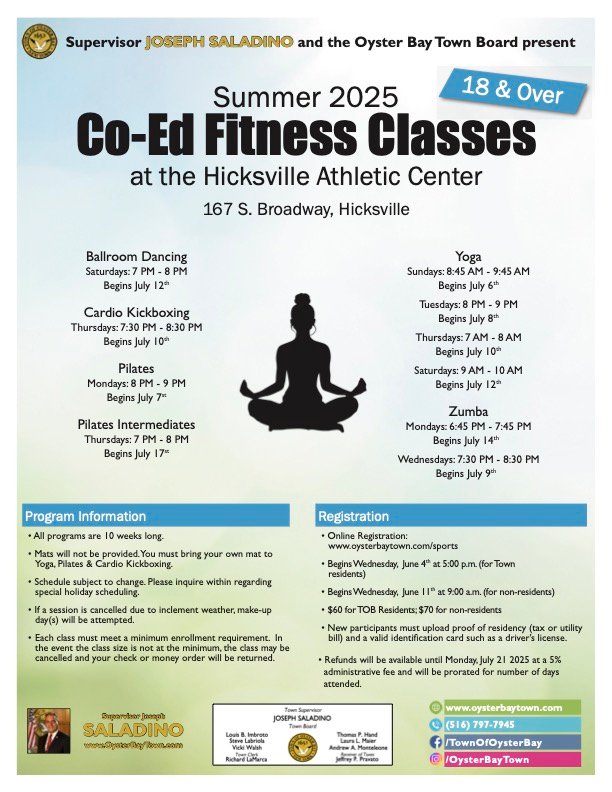

Registration opening for Town of Oyster Bay co-ed fitness classes – LI Press

Oyster Bay Town Council Member Laura Maier announces that registration is opening for the town’s co-ed fitness classes for the summer season at the Hicksville Athletic Center.

Starting in early July, these 10-week programs offer a fun way to stay fit and meet new people. Open to everyone ages 18 and older, the classes cover everything from cardio kickboxing to yoga and ballroom dancing.

“Our great summer programs provide a fun, energizing way for residents to stay active while joining with friends or meeting new people,” Maier said. “Whether you’re into high-energy workouts like cardio kickboxing or prefer something more relaxing like yoga, there’s a class for everyone to enjoy!”

This summer, participants can once again choose from a variety of fitness options:

Visit oysterbaytown.com/sports to sign up. Registration opens Wednesday, June 4, for residents and June 11 for non-residents. Town of Oyster Bay residents who have not used the signup portal will need to upload proof of residency (tax or utility bill) and a valid ID, like a driver’s license. Non-residents may register at a slightly higher fee.

Participants must bring their own mats for yoga, pilates and cardio kickboxing. Class schedules are subject to change, and if a session is cancelled, make-up days will be offered.

For more information, call (516) 797-7945 or email tobparks@oysterbay-ny.gov.

Post an Event

View All Events…

Leave a Comment

What Is Eft Tapping? How To Do It and Benefits – Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials

Advertisement

It involves tapping specific points on your body while focusing on an emotion or issue you want to release

Could a few well-placed taps on your body be what it takes to help reduce stress and even ease physical pain? It may sound unbelievable, but there’s some compelling science behind the Emotional Freedom Technique, more commonly known as EFT tapping.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

In fact, a 2022 review of more than 50 research studies found that EFT tapping is moderately to largely effective in managing a variety of conditions, including anxiety, phobias, depression, PTSD, insomnia, pain and athletic performance.

Functional medicine specialist Melissa Young, MD, explains what EFT tapping is, how to do it and what it may be able to do for you.

It’s hard to imagine that using your fingers to tap, tap, tap on your eyebrow or clavicle could help melt away stress and relieve some of your pain, but that’s the idea behind Emotional Freedom Technique.

This holistic, evidence-based practice is one that you can do on your own, anywhere and at any time, without any special tools. You use your fingertips to tap on specific points on your body — mainly on your head and face — while you focus your mind on a particular issue or emotion.

“I like to think of it as a blend of modern psychology and acupressure points to lower stress and help with issues like anxiety, mood and even pain,” Dr. Young says. “It’s a nice blend of connecting the mind and body to help calm stress.”

EFT tapping, which was developed in the 1970s and ’80s, is rooted in the idea of acupoints. According to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), 12 primary meridians (channels) carry energy throughout the body. Acupoints sit along these meridians and can be stimulated by acupuncture or acupressure.

Advertisement

“In EFT tapping, we utilize nine of those points,” Dr. Young says. The idea is that tapping on these points helps to reduce stress and anxiety and, as some proponents believe, to balance the body’s energy system.

EFT tapping might simply make you feel better, period, whether or not you’re feeling bad to start with. One study found that at the time it was performed, EFT tapping increased happiness by 31%.

“Another study showed that it can lead to up to a 43% decrease in cortisol levels, which is one of the body’s primary stress hormones,” Dr. Young points out, “so that’s pretty impressive.”

Other studies on EFT tapping have shown that it may be able to help relieve symptoms of various conditions:

But it’s important to note that EFT tapping shouldn’t take the place of seeking medical care from a licensed healthcare provider and following any prescribed treatment plans. A 2023 commentary on a review of research on EFT tapping for PTSD noted that many studies use self-reported diagnoses and symptom relief when publishing results. This means that some EFT research relies on individuals, not healthcare providers, to confirm their diagnoses and to assess their changes in symptoms, and could be biased.

If you think you have a specific health condition, or already have a diagnosis, you should discuss the use of EFT tapping to manage your symptoms with your provider before beginning.

Like breathwork techniques, EFT tapping is relatively easy to learn and perform, and you can do it just about anywhere — meaning that if you’re in the midst of a busy or stressful day, all you need to do is duck out for five to 15 minutes of solitude. It’s also:

Ready to learn more about what it is and how to do it? Let’s dive in.

EFT tapping (literally) taps into nine acupoints in a specific sequence. But it’s not all tapping: The tapping sequence is bookended by an exercise in thinking about the issue that you want to address, whether it’s stress, anger, pain, cravings or something else.

Advertisement

Dr. Young walks us through how to do EFT tapping.

The first step to EFT tapping isn’t tapping at all. First, identify the emotion or problem that’s bothering you in this moment, whether it’s anger, stress, anxiety, depression or even pain.

“I like to call this ‘tuning in,’” Dr. Young says. “You may want to put a hand on your chest and close your eyes as you focus inward on the emotion or issue that you want to deal with.”

Once you’ve identified the emotion or issue that you’re facing, rate its intensity on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is “totally fine” and 10 is “the absolute worst.” Setting a benchmark for your state of mind before the EFT tapping allows you to better assess how you feel once you’re done with the process.

Adopt a phrase that acknowledges both the issue you’re facing and your own self-acceptance, for example, “Even though I feel stress in my body, I fully and deeply accept myself.”

Your setup statement should be self-reflective and about what’s going on with you, rather than focused on someone else or the environment around you.

“In today’s society, we tend to want to push things away,” Dr. Young notes. “It’s about what you’re feeling and being able to acknowledge, ‘I am feeling this, but it’s OK and I accept myself despite it.’”

Advertisement

You’re now ready to work your way through nine tapping points.

As you start the tapping sequence, continue to repeat the phrase that you’ve come up with and expand on it as you go through each tapping point. Variations might include, for example, “I feel stress in my body, but I am open to releasing it now,” and, “Even though I have all this stress in my body, I am choosing to let it go.”

Now, you’re ready to begin. Gently tap each of the following points seven to nine times apiece, slowly working your way through them and repeating variations on your setup statement as you go.

“As you tap, continue to think about the stress in your life and in your body,” Dr. Young instructs. “This is a time we want to bring up those feelings. We want to feel them because we’re working on that mind/body connection.”

Advertisement

Dr. Young recommends completing five to seven rounds of the tapping sequence. When you’re done, finish by assessing the final intensity of the emotion or problem that you were trying to address through EFT tapping.

“If that feeling hasn’t resolved or calmed, or if you feel like you still have more work to do, you can certainly do more rounds than that,” she says.

With that, though, comes an important caveat: If at any time you feel overwhelmed by the intensity of your feelings and can’t seem to make a dent in them on your own, reach out to a healthcare professional, like a therapist or a family care provider.

You may choose to tap on only one side of your body (for example, below the left pinky, inside the left eyebrow, etc.) or on both sides (for example, below the left pinky, then below the right pinky, inside the left eyebrow and then inside the right eyebrow, and so on).

“It’s all up to your personal preference, so if you’re right- or left-handed or one feels better than the other, just choose that,” Dr. Young says. “There’s no data on this, but I’m partial to tapping on both sides so that both sides of the brain are getting input.”

But whichever you choose, just try to remain consistent throughout your tapping session.

While this therapy hasn’t become as commonplace as other traditional Chinese medicine-based techniques, like acupuncture, there’s no harm in adding EFT tapping to your daily or weekly routine. In fact, the more often you practice EFT tapping, the more helpful it may be. That’s not because practice makes perfect (what is “perfect,” anyway?!), but because your body starts to get used to it and welcome it as a means of calming down.

“Being consistent in your practice helps your nervous system to better shift out of fight-or-flight mode (aka sympathetic mode) and into rest-and-digest mode (aka parasympathetic mode),” Dr. Young explains.

“Even practicing in smaller amounts of time throughout the course of a day can be helpful.”

Learn more about our editorial process.

Advertisement

This treatment may reduce stress, relieve pain and allergy symptoms, and help with sinus pressure

Supplements with colloidal silver offer no proven health benefits and could be harmful

Connecting with the Earth and its energy might improve your mental and physical health — but it’s not a cure-all

These terms are becoming outdated as providers turn to an ‘integrative’ approach instead

This alternative medicine is based on the premise that diluted ingredients will treat symptoms

Ayurveda is a 5,000-year-old medical system

These ancient practices are all about mind/body balance

Fulvic acid is a chemical compound formed by the breakdown of soil

If you’re feeling short of breath, sleep can be tough — propping yourself up or sleeping on your side may help

If you fear the unknown or find yourself needing reassurance often, you may identify with this attachment style

If you’re looking to boost your gut health, it’s better to get fiber from whole foods

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment

These parents are 'unschooling' their kids. What does that mean? – USA Today

The days are about to look very different for most parents in a few weeks as schools let out for the summer.

But for Christina Franco, 39, summer days in her upstate New York home are no different than any other day during the school year because her five kids are “unschooled.”

Instead of going to traditional school or following a homeschool curriculum, Franco’s children decide what they want to learn every day.

For her three younger children, who are 5, 6 and 9, that typically means playing outside for most of the day. For her 13-year-old, it means drawing or practicing the drums for hours a day. Her 17-year-old is preparing for graduation while working as a lifeguard.

Whenever her kids are ready to learn, Franco plans a lesson or a field trip to museums, historical sites or mountains nearby. But there are no grades, no tests and no curriculum.

“My goal for them is for them to love learning,” Franco said. “It’s realizing you can educate your child beyond the school model.”

Unschooling videos have amassed millions of views on social media as fascination with the educational movement grows. Even Kourtney Kardashian said sending kids to school felt “so dated” while speaking with her sister during a recent episode of the “Khloe in Wonder” Land podcast. Some parents say their children are thriving in the unschooling environment, fueling their confidence and desire to learn.

But not all students find success in unschooling. Some former students say the lack of structure and accountability can lead to educational neglect if parents don’t have the resources to make it work. Some kids who were unschooled feel they were left unprepared for adulthood and had fewer career opportunities.

“It takes an incredible amount of time, resources and energy to do it well and there is an equity problem to that,” said Jonah Stewart, interim executive director of the Coalition for Responsible Home Education, who was homeschooled. “While we see many important and very beneficial uses for (home education), there are situations where it can be used for neglect and abuse.”

Self-directed education, commonly known as unschooling, is a form of homeschooling that is based on activities and life experiences chosen by the child, according to the Alliance for Self-Directed Learning (ASDE), a nonprofit dedicated to increasing awareness and accessibility to unschooling.

Education experts say parents and caregivers unschool differently. Some take a few pages from the homeschooling curriculum and carve out lessons for their children. Others attend micro-schools or “free schools,” where unschooled children are grouped together in a “nature school” or “outside school” under the guide of parents or teachers, said Daniel Hamlin, associate professor of education policy at the University of Oklahoma.

Some parents dive into unschooling with no structure and don’t initiate any semblance of traditional education unless explicitly asked by their children.

What health & wellness means for your family: Sign up for USA TODAY’s Keeping It Together newsletter.

“The thing we all have in common in unschooling is that the young person is in charge and has the autonomy of what it looks like and the parent is the support and guide,” said Bria Bloom, staff member and organizer at ASDE. She was unschooled growing up and is now unschooling her two children, who are 14 and 2.

There are various reasons why parents and caregivers decide to unschool their children. Many say it’s to shield them from the bullying and violence that sometimes play out in a traditional educational setting. Some don’t want their children to be forced into learning things they don’t find interesting. Others say they don’t trust educators to focus on their children if they have special learning needs.

While some parents claim unschooling produces happier students, Hamline said more research is needed.

“People come into this topic with their own biases in mind. People have these presuppositions about whether it’s good or bad and the reality is that it’s a very dynamic and diverse sector of American education,” Hamline said. “There’s all this change happening and there isn’t a lot of good data to lean heavily into one perspective or the other.”

Unschooling may work for some families but some argue it’s also vulnerable to unintended consequences such as abuse and educational neglect.

Erin Lauraine, 42, was unschooled throughout her childhood and adolescence in Las Vegas. Although her parents called it “homeschooling,” she said there was no curriculum, benchmarks, tests or progress reports.

Instead of schoolwork, Lauraine filled her day with doing household chores, watching cartoons and working at her parents’ manufacturing plant.

It was “absolutely” educational neglect, she said.

“It took me a long time to admit that,” said Lauraine, who now lives in Dallas. “I was denied access to an education and denied access at an age when my brain was primed to learn.”

Laws to prevent abuse and neglect when a child is educated at home, whether it’s unschooling or homeschooling, vary widely from state to state, said Stewart, from the Coalition for Responsible Home Education. In New York, Franco is required to notify the superintendent of the intent to homeschool, compose and file instruction plans and turn in quarterly reports about her unschooled her children.

But about a dozen states don’t have any safety nets to ensure a child receives a proper education, Stewart said. Parents aren’t required to notify the school, provide instruction plans or send in regular assessments.

Families can also skirt around state laws by enrolling children in certain “umbrella schools,” which offer a way for parents to meet compulsory attendance laws, Stewart said. While some umbrella schools can help with recordkeeping and submitting state paperwork, most don’t provide academic oversight or accountability.

The lack of check-ins with the student or family also makes it harder to provide social services, Stewart said.

“A lot of social services work is predicated on continued engagement,” she said. “When the opportunity for contact is foreclosed, the odds of that family receiving the intervention it needs are lower.”

While Franco’s oldest son flourished academically, she said the social pressures of middle school weighed him down and eroded his confidence. That weight lifted once her son left traditional schooling in seventh grade and began unschooling.

After graduating, Franco’s son plans on taking a gap year to figure out his next chapter. He’s considering an apprenticeship as a mechanic or college for a mechanical engineering degree.

“I encouraged him that he doesn’t need to make the decision, right now,” Franco said. “He realized he can learn anything he wants to learn.”

While her son’s future appears full of possibilities, Lauraine and other former unschooling students felt lost entering adulthood.

Lauraine knew how to operate a blowtorch and balance her parents’ checkbook, but she didn’t know who she was and what she wanted to do with her life. Adulthood “was pretty terrifying,” she said.

“It was really trial and error trying to figure something out,” she said. “(My parents) prioritized the practical experience but didn’t understand the psychological consequences of adulthood-type exposures on kids and the meaning put into those experiences.”

Lauraine eventually got her GED when she was 35, which she said was an emotional experience, and graduated this year with her bachelor’s degree in behavioral science.

She commends parents who want to take a proactive role in their child’s education, but advocates for stronger state regulations to prevent educational neglect.

“My entire life is being a late bloomer,” Lauraine said. “I don’t believe my parents are bad people. I believe that their intentions, while they were good, were really shortsighted.”

Adrianna Rodriguez can be reached at adrodriguez@usatoday.com.

Leave a Comment

Association between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health with perceived work stress, work–family conflict and job satisfaction as psychosocial mediators: a national study in China – Frontiers

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 29 May 2025

Sec. Personality and Social Psychology

Volume 16 – 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1561653

This article is part of the Research TopicWorld Mental Health Day: Mental Health in the WorkplaceView all 22 articles

Background: Nonstandard work schedules are prevalent across the industrialized world. While prior research indicates nonstandard work schedules lead to poor mental health, little research has explored the psychosocial pathways underlying the association between work schedule and mental health. This study aimed to fill this gap by testing for the mediating roles of perceived work stress, perceived work–family conflict and perceived job satisfaction in the association between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health.

Methods: Using a nationally representative sample of data from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) in 2021 (N = 1857), and using the Process v4.1 for SPSS, we examined the association between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health and estimated the independent and joint mediation effects of perceived work stress, perceived work–family conflict and perceived job satisfaction.

Results: A total of 1857 employees participated in the final analysis. Of these, 1,331 employees (71.7%) work fixed day shifts, 24 employees (1.3%) work fixed night shifts, 206 employees (11.1%) work rotating shifts, 243 employees (13.1%) work irregular schedules and 53 employees (2.8%) work other schedules. Nonstandard work schedule was negatively correlated with employees’ self-rated mental health and perceived job satisfaction, and positively correlated with perceived work stress and work–family conflict (p < 0.001). The independent mediation effects of perceived work stress, perceived work–family conflict and perceived job satisfaction was 17.3, 22.4 and 16.5%, respectively. The joint effect of all three mediators mediated about 36.2% of the relationship between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health. Sensitivity analyses revealed that rotating shift (p < 0.05) and irregular schedule (p < 0.001) were negatively associated with employees’ self-rated mental health, perceived job satisfaction fully mediated the association between rotating shift and employees’ self-rated mental health, while perceived work stress, work–family conflict and job satisfaction jointly and partially mediated the association between irregular schedule and employees’ self-rated mental health (the joint effect of all three mediators mediated about 42.4% of the relationship).

Conclusion: Perceived work stress, perceived work–family conflict and perceived job satisfaction mediated the relationship between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health. The findings advance understanding of the psychosocial mechanisms underlying the association between work schedule and mental health.

Countries around the world have shifted to a 24/7 economy (an economy that operates 24 h per day and 7 days per week), which means increasing numbers of employees are working nonstandard hours (Smith et al., 2023). Nonstandard work schedules are generally defined in the literature as work that occurs outside of the traditional daytime and weekly Monday to Friday 9 am–5 pm schedule (Smith et al., 2023; Taiji and Mills, 2020; Totterdell, 2005). Nonstandard work schedules are known to affect mental health, not only through biological pathway, in which the body’s circadian rhythms are affected and thus leading to physiological disturbances and the inability to cope, but also through social pathway (Haines et al., 2008). However, current research and evidence on the social or psychosocial pathway by which nonstandard work schedules may lead to poor mental health is limited. To our best knowledge, aside from three studies to date have attempted to assess the mediating role of work–family conflict in the association between nonstandard work schedules and mental health, which were conducted in Australia (Zhao et al., 2021a), Canada (Haines et al., 2008) and the USA (Cho, 2018), no study has assessed other social or psychosocial mediators in the association between nonstandard work schedules and mental health. Given to Totterdell’s (2005) proposal that more research is needed to elucidate the precise biological, psychological, and social pathways, we believe that more research is needed to examine the potential psychosocial mechanisms underlying the association between nonstandard work schedules and mental health.

In this study, using data from the nationally representative Chinese General Social Survey, we attempted to address the identified gaps by assessing the mediating roles of perceived work stress, perceived work–family conflict and perceived job satisfaction in the association between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health.

Our study contributes to the literature by demonstrating the psychosocial mechanisms of perceived work stress, perceived work–family conflict and perceived job satisfaction in the study of association between work schedule and mental health, since little research has explored the psychosocial pathways underlying the association between work schedule and mental health. Our study is the first, to our knowledge, to explicitly test and confirm the mediating roles of perceived work stress and job satisfaction in the association between work schedule and mental health. This study also used a unique data set from a nationally representative survey (Wang et al., 2024) which the latest 2021 wave adds the quality of work topical module. To our knowledge, this is the first nationally representative study in China to investigate work schedules.

Employee mental health is a central issue in today’s global workplace (Kim K. Y. et al., 2023; Kim S. E. et al., 2023). Poor mental health can affect employees’ work efficiency and job performance (Chen et al., 2022). Depressive symptoms are frequent and cause considerable suffering for the employees as well as financial loss for the employers (Theorell et al., 2015). Furthermore, mental health problems have been acknowledged as a major public health issue (Zhao et al., 2019). For example, depression accounts for 4.3% of the global burden of disease and incidence, with mental disorders worldwide predicted to cost US $16.3 million by 2030 (Torquati et al., 2019). This suggests that understanding the social determinants of employees’ mental health is important.

Nonstandard work schedules have long existed (Bolino et al., 2021). Because of the demand for round-the-clock service from various vital sectors such as health, security, transport and communication, the technical need for maintaining continuous process industries, and the development in industry and social sector, nonstandard work schedules become more and more inevitable (Vogel et al., 2012). Nonstandard work schedules are prevalent across the industrialized world (Kim et al., 2025; Wang, 2023), although their prevalence is difficult to compare due to the use of different samples and definitions (Li et al., 2014). In the UK, data from the UK Household Longitudinal Study showed that 28.2% of employees worked nonstandard hours (Weston et al., 2024). In Sweden, data from the Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health showed that 19.72% of Swedish workers have a shift work with nights, 24.49% of Swedish workers have a shift work without nights, and only 55.78% of Swedish workers have a daywork (Tucker et al., 2021). In South Korea, data from the Korea Labor and Income Panel Survey showed that 10.4% of workers worked shift work (Jung et al., 2022).

A number of studies have provided evidence of an association between nonstandard work schedules and mental health (Brown et al., 2020; Han, 2023; Harris et al., 2024; Lee et al., 2016; Niedhammer et al., 2022). Nonstandard work schedules can disrupt circadian rhythms and contribute to sleep disturbances (Coelho et al., 2023; Frazier, 2023; Jeon and Kim, 2022; Kim K. Y. et al., 2023; Kim S. E. et al., 2023; Sateia, 2014; Weng and Chang, 2024; Weston et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024). Consequently, sleep disturbances frequently underlie the mental health consequences of nonstandard work schedules, and mediated the association between nonstandard work schedules and mental health (Brown et al., 2020; Cheng et al., 2023; Das and Palo, 2024; Frazier, 2023; McNamara and Robbins, 2023; Zhang et al., 2022).

Nonstandard work schedules may negatively associate with mental health through channels other than sleep as well (Chen et al., 2025; Sierpińska and Ptasińska, 2023). However, besides sleep disturbances, much less is known about what is a clear mechanism underlying the association between nonstandard work schedules and mental health. In the following sections, we propose and outline the theoretical underpinnings linking nonstandard work schedules to mental health with the focus on the psychosocial pathways of perceived work stress, work–family conflict and job satisfaction.

Theoretically, the job demands-resources (JD-R) model is one of the most popular and influential models of work stress in the literature (Roskams et al., 2021), which provides a theoretical framework linking nonstandard work schedules, stress and mental health. The model clearly expands earlier models of work-related stress and burnout, such as Karasek’s (1979) job demands-control model (which predicts and explains that job strain, occurs when job demands are high and job decision latitude is low, is related to symptoms of mental strain) (Demerouti et al., 2001; Karasek, 1979). Job demands refer to those physical, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical or mental effort and are therefore associated with certain physiological and psychological costs (e.g., exhaustion), and nonstandard work schedule is clearly identified as a typical example of job demands (Demerouti et al., 2001; Roskams et al., 2021). The demanding aspects of work (e.g., nonstandard work schedules) lead to exhaustion (Hong, 2025; Ong and Johnson, 2023), which is a state that closely resembles traditional stress reactions studied in occupational stress research, conceptually (Demerouti et al., 2001). Further, a lack of job resources leads to a state of disengagement, and the combination of exhaustion and disengagement is symptomatic of burnout (Romo et al., 2025; Roskams et al., 2021), which is in turn associated with various negative outcomes such as impaired mental health (Chen et al., 2025; Fix and Powell, 2024; Gawlik et al., 2025; Kerr et al., 2025; Koutsimani et al., 2019).

Unsurprisingly, a number of quantitative studies have found that working nonstandard hours can lead to higher levels of work stress (Bolino et al., 2021; Castillo et al., 2020; Golden, 2015; Son and Lee, 2021; Yuan and Fang, 2024). From a functional neuroimaging perspective, working on long-term shift had decreased brain functional activity and connectivity in the right frontoparietal network, which were associated with burnout, stress, and depression conditions (Dong et al., 2024).

In turn, a robust body of literature has indicated that perceived work-rated stress is a strong predictor of mental health (Chireh et al., 2023; Du et al., 2023; Niedhammer et al., 2021; Theorell et al., 2015). One possible channel through which work stress affect mental health is that work stress can affect sleep quality (Xu et al., 2024; Matti et al., 2024), although Son and Lee (2021) found that high work stress had stronger associations with suicidal ideation than poor sleep quality in shift workers.

Given the Job Demands-Resources model, and given that nonstandard work schedules can lead to higher levels of work stress and the clear indication that perceived work stress is a risk factor for mental health, we anticipate that perceived work stress will mediate the association between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health.

Theoretically, the work–family conflict model provides a useful theoretical framework for understanding the mechanism through which nonstandard work schedules affect workers’ mental health (Cho, 2018; Haines et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2021a). The work–family conflict model proposed that work–family conflict is a form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect, and any role characteristic that affects a person’s time involvement, strain, or behavior within a role can produce conflict between that role and another role (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985). Shift work may simultaneously produce both time-based and strain-based work–family conflict (Cho, 2018; Haines et al., 2008; Wöhrmann et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2021a). Nonstandard work schedules require employees to work at times that are most socially valuable, such as evenings and weekends, during which most family and other social activities take place, that results in time-based work–family conflict (Wöhrmann et al., 2020). Working nonstandard hours often also leads to sleep deprivation and fatigue, which, in turn, leads to irritability and strain in family interactions, that results in strain-based work–family conflict (Zhao et al., 2021a).

Empirical studies have found the association between nonstandard work schedules and work–family conflict (Al-Hammouri and Rababah, 2023; Ambiel et al., 2024; Lambert et al., 2023; Tammelin et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2021b), and the strength of this association varies significantly between countries (Taiji and Mills, 2020).

In addition, work and family roles and the balance between the two are important for workers’ mental health (Wang et al., 2007), and the association between work–family conflict and mental health was moderated by socioeconomic status, family structure, job conditions, educational mismatch, resilience and social support (Huang et al., 2024; Lee et al., 2022; Song et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2020). Given these considerations, we anticipate that working nonstandard schedules will lead to greater perceived work–family conflict, which in turn will augment the risk of experiencing poor mental health.

Theoretically, there is an inherent factor causing shift workers to be less satisfied with their jobs than day workers, and the dissatisfaction may be created by the shift workers’ non-congruent role in society in relationship to the time schedule of the majority of the community (Dunham, 1977). Specifically, Dunham’s (1977) theoretical analysis is that “there appears to be a 24-h cyclical rhythm of not only bodily functions but social and personal functions structured by community practices. The shift worker is often out of phase with the rest of the community in this cycle and becomes the deviant within the society. This deviancy ‘costs’ the shift worker through adjustment problems with important non-physiological functions.”

The literature has suggested that nonstandard work schedules may lead to feelings of job dissatisfaction. Among nurses and physicians, work schedule conflicts were one of the least satisfying aspects of work (House et al., 2022), and comparing to day shift nurses, irregular shift nurses (Bagheri Hosseinabadi et al., 2019), fixed night shift nurses and rotating shift nurses (Kim et al., 2024) suffered from lower job satisfaction. In addition, crew scheduling is one of the antecedents of employee dissatisfaction in airlines (Han et al., 2024).

In turn, a large body of quantitative research has indicated that job satisfaction contributes to mental health (Chireh et al., 2023; Chong et al., 2023; Jilili et al., 2023; Monahan et al., 2023; Wang and Derakhshan, 2025; Worley et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2024; Yun et al., 2024; Zhou et al., 2023), coving a variety of occupations in different countries.

Given Dunham’s (1977) theory, and given that nonstandard work schedules may lead to feelings of job dissatisfaction and the clear indication that job satisfaction contributes to mental health, we anticipate that perceived job satisfaction will mediate the association between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health.

In summary, theories and previous research findings provide grounds for anticipating that nonstandard work schedules may affect mental health, and perceived work stress, perceived work–family conflict and perceived job satisfaction may account for the association between nonstandard work schedules and mental health. However, little research has explicitly test and confirm the psychosocial pathways underlying the association between work schedule and mental health. To examine the potential psychosocial mechanisms in the association between nonstandard work schedules and mental health, based upon prior research and theoretical analysis, the present study tests the following hypotheses among a nationally representative sample from China:

H1: Nonstandard work schedules will be negatively associated with employees’ self-rated mental health.

H2: The association between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health will be mediated by perceived work stress.

H3: The association between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health will be mediated by perceived work-family conflict.

H4: The association between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health will be mediated by perceived job satisfaction.

We use the latest data of Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) in 2021. The CGSS is the earliest national representative continuous survey project run by academic institution in China mainland. It collects quantitative data about measures of social structure, quality of life, and underlying mechanisms linking social structure and quality of life, to systematically monitor the changing relationship between social structure and quality of life in China (Bian and Li, 2012). CGSS was launched in 2003 and had included 12 waves so far: 2003, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2017, 2018 and 2021. Latest 2021 wave added quality of work topical module, which exactly fulfill our need for research.

This study used the latest wave of CGSS, which surveyed residents in 19 provinces of China. The original sample size was 8,148, of which 1,978 were employees. After excluding observations with missing data on at least one of the study variables in addition to income, the final sample was restricted to 1,857 observations. Income as a control variable has 108 missing values still and we impute them using univariate imputation (Royston, 2004) through other control variables in order to reduce the loss of sample size. Among the 1,857 observations, males accounted for 53.15% and females accounted for 46.85%. In terms of age, 19.55% were between 18 and 29 years old, 28.76% were between 30 and 39 years old, 25.15% were between 40 and 49 years old, 20.19% were between 50 and 59 years old, and 6.35% were 60 years old or older. In terms of education level, 11.58% had primary school education or below, 25.47% had junior high school education, 20.62% had high school education, 21.16% had a junior college degree, 17.82% had a bachelor’s degree, and 3.34% had a graduate degree. In addition, in terms of work schedule, 71.67% had a fixed day shift, 1.29% had a fixed night shift, 11.09% had a rotating shift, 13.09% had an irregular schedule, and 2.85% had other schedules.

In this study, the outcome variable is self-rated mental health, the explanatory variable is nonstandard work schedules, the mediating variables are perceived work stress, perceived work–family conflict and perceived job satisfaction, the control variables are self-rated physical health, overtime work, changing jobs during COVID-19 and demographic characteristics (include gender, age, education, income, political status, marital status, family economic status and regions).

Consistent with previous research (Cho, 2018), self-rated mental health is measured by asking the question “During the past 4 weeks, how often you felt depressed?” Response options included “always,” “often,” “sometimes,” “rarely” and “never.” Responses were coded from 1 = “always” to 5 = “never.” Higher numbers indicate greater levels of mental health.

2021 CGSS quality of work module asks the question, “Which of the following best describes your usual work schedule?” Response options included “fixed day shift,” “fixed night shift,” “rotating shift,” “irregular schedule” and “other work schedules.” Consistent with previous research (Castillo et al., 2020; Cho, 2018; Haines et al., 2008; Han, 2023; Kachi et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2016; Tammelin et al., 2017; Weston et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2021b), fixed day shift was categorized as “standard work schedules” and was coded as 0, while other four options were categorized as “nonstandard work schedules” and were coded as 1. In addition to this broad binary measure, each response option was a category of work schedules in sensitivity analysis.

Perceived work stress is measured by asking the question “How often do you find your work stressful?” Response options included 1 = “always,” 2 = “often,” 3 = “sometimes” and 4 = “never.” Responses were reverse coded in this study so that higher values indicate more perceived work stress.

Consistent with previous research (Cho, 2018), perceived work–family conflict is measured by asking the question “In general, how often you felt that your job interfere with your family life?” Response options included 1 = “always,” 2 = “often,” 3 = “sometimes,” 4 = “rarely” and 5 = “never.” Responses were reverse coded in this study so that higher numbers indicate more perceived work–family conflict.

Perceived job satisfaction is measured by asking the question “In general, how satisfied would you say you are with your job?” Response options included 1 = “very satisfied,” 2 = “moderately satisfied,” 3 = “neither satisfied nor dissatisfied,” 4 = “a little dissatisfied” and 5 = “very dissatisfied.” Responses were reverse coded in this study so that higher numbers indicate greater levels of perceived job satisfaction.

Self-rated physical health is measured by asking the question “In general, how would you rate your physical health?” Response options included “Poor,” “Fair,” “Good,” “Very good” and “Excellent.” Responses were coded from 1 = “poor” to 5 = “excellent.” Higher numbers indicate greater levels of physical health.

Overtime work is measured by asking the question “Did you work overtime last week?” Respondents who responded “no” were coded as 0 and respondents who responded “yes” were coded as 1.

Changing jobs during COVID-19 is measured by asking the question “Compared to before the COVID-19, which of the following descriptions best fits your current situation?” Response options included “I did not change my job,” “I lost my job due to COVID-19, but I have a new job now,” “I did not have a job before COVID-19, but now I have a job” and “I changed my job, but not because of COVID-19.” The first option was categorized as “did not change jobs during COVID-19” coded 0, and other options were categorized as “change jobs during COVID-19” coded 1.

Demographic characteristics include gender (0 = males, 1 = females), age (equals “2021 – birth year”), education (1 = primary school or below, 2 = junior high school, 3 = high school, 4 = associate/junior college, 5 = bachelor’s, 6 = graduate), income (equals “ln (1 + personal annual income),” and was winsorized at 1 and 99% levels), political status (1 = Communist Party members), marital status (1 = currently married), family economic status (1 = far below average, 2 = below average, 3 = average, 4 = above average, 5 = far above average, compared with local families in general) and regions. Eastern region (reference) equals one if respondents’ residence is Beijing, Hebei, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong or Liaoning, and zero otherwise. Central region equals one if respondents’ residence is Shanxi, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei or Hunan, and zero otherwise. Western region equals one if respondents’ residence is Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Chongqing, Shaanxi, Gansu or Ningxia, and zero otherwise.

SPSS 24.0 was used in this study. First, we conducted descriptive analysis for each of the study variables to understand the overall sample. Second, we computed the correlation matrix of our dependent variable, main independent variable, and mediators. Third, we conducted common method bias test to assess the potential for common method variance. Forth, we examined the association between nonstandard work schedules and self-rated mental health and estimated the independent and joint mediation effects of perceived work stress, work–family conflict and job satisfaction, using the Process v4.1 for SPSS (Hayes, 2017; Preacher and Hayes, 2008). We used 10,000 bootstrapped resamples to describe the 95% confidence intervals for effect that are statistically significant if their confidence intervals do not contain zero. Fifth, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to divide and compare each group of work schedules.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for all study variables. The mean values of self-rated mental health, perceived work stress, work–family conflict and job satisfaction were 4.13 (SD = 0.93), 1.95 (SD = 0.94), 1.98 (SD = 1.05), and 3.67 (SD = 0.84), respectively. The mean value of self-rated mental health among standard work schedules and non-standard work schedules is 4.18 and 4.00, respectively (effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.20, p < 0.001). The mean value of perceived work stress among standard work schedules and non-standard work schedules is 1.90 and 2.07, respectively (effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.18, p < 0.001). The mean value of perceived work–family conflict among standard work schedules and non-standard work schedules is 1.90 and 2.17, respectively (effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.26, p < 0.001). The mean value of perceived job satisfaction among standard work schedules and non-standard work schedules is 3.73 and 3.50, respectively (effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.29, p < 0.001). T-tests show a lower level of self-rated mental health and perceived job satisfaction, and a higher level of perceived work stress and work–family conflict in non-standard work schedule group, compared with the standard work schedule group.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (N = 1,857).

Correlation matrices for dependent, main independent and mediator variables are reported in Table 2. As shown in Table 2, the correlations between self-rated mental health, non-standard work schedule, perceived work stress, perceived work–family conflict and perceived job satisfaction are all significant at the p < 0.001 level.

Table 2. Correlation matrix for dependent, main independent, and mediator variables.

Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to assess the potential for common method variance. The results showed that the variance explained by the first factor was 32.192%, which was below the acceptable threshold of 40%. Therefore, this suggests that significant common method bias was not present in this study.

To examine the association between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health and estimate the independent and joint mediation effects of perceived work stress, work–family conflict and job satisfaction, we applied Hayes’s (2017) SPSS PROCESS v4.1 (Component Model 4), with 10,000 replicates and 95% CI. The results are shown in Table 3. First, nonstandard work schedules could significantly and negatively predict mental health (β = −0.188, p < 0.001), the total effect of nonstandard work schedules on self-rated mental health is −0.188 (Bootstrap 95% CI: −0.277, −0.099), and the direct effect of nonstandard work schedules on self-rated mental health is −0.120 (Bootstrap 95% CI: −0.208, −0.033), accounting for 63.8% of the total effect. Second, the independent mediation analysis showed that perceived work stress (accounting for 17.3% of the total effect), perceived work–family conflict (22.4%), and perceived job satisfaction (16.5%) significantly mediated the association between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health. Third, the joint effect of perceived work stress, work–family conflict and job satisfaction mediated 36.2% of the total effect of nonstandard work schedules on employees’ self-rated mental health (Figure 1).

Table 3. Mediation of association between work schedule and mental health (N = 1,857).

Figure 1. Results of the simultaneous mediation model.

Although many of previous studies lumped ‘any arrangement of daily working hours that differs from the standard daylight hours’ together labeled “nonstandard work schedule” or “shift work” and did not divide different types of nonstandard work schedules in their analysis given the small share of participants engaged in each of the detailed nonstandard work schedules (Castillo et al., 2020; Haines et al., 2008; Han, 2023; Jung et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2016; Tammelin et al., 2017; Weston et al., 2024), we are aware that dividing and comparing each group of work schedules would strengthen our findings. The mean values of self-rated mental health among fixed day shift, fixed night shift, rotating shift, irregular schedule and other schedules are 4.18, 4.17, 4.03, 3.95 and 4.00, respectively, but the differences of the mean values are significant only within two pairs (fixed day shift vs. rotating shift; fixed day shift vs. irregular schedule) due to the small sample size of “fixed night shift” (n = 24) and “other schedules” (n = 53). As shown in Table 4, controlling for the studied sociodemographic variables, rotating shift was significantly and negatively associated with employees’ self-rated mental health (β = −0.132, p < 0.05) and perceived job satisfaction (β = −0.156, p < 0.01), irregular schedule was significantly and negatively associated with employees’ self-rated mental health (β = −0.257, p < 0.001) and perceived job satisfaction (β = −0.251, p < 0.001), and significantly and positively associated with perceived work stress (β = 0.328, p < 0.001) and perceived work–family conflict (β = 0.473, p < 0.001). Furthermore, perceived job satisfaction fully mediated the association between rotating shift and employees’ self-rated mental health, and perceived work stress, perceived work–family conflict and perceived job satisfaction independently and jointly mediated the association between irregular schedule and employees’ self-rated mental health (the proportion of the joint mediation effects is 42.4%).

Table 4. Sensitivity analysis: regression coefficients of regression models (N = 1,857).

The aim of our study was to extend the line of the work schedule—mental health ideation scholarship by considering the role of psychosocial pathways underlying this association in a nationally representative sample in China. Specifically, using data from the latest 2021 wave of Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS), we examine the mediating effects of perceived work stress, work–family conflict and job satisfaction on the relation between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health.

After controlling for self-rated physical health, overtime work, changing jobs during COVID-19 and demographics, baseline analyses revealed that nonstandard work schedules had a negative relationship with employees’ self-rated mental health, thereby Hypothesis 1 was supported. This finding aligns with previous research that reported significant associations between nonstandard work schedules and mental health (Cho, 2018; Frazier, 2023; Haines et al., 2008; Han, 2023; Lee et al., 2016; Niedhammer et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2021a).

Furthermore, supporting Hypotheses 2, 3 and 4, we found that working nonstandard schedules was associated with increases in perceived work stress and work–family conflict as well as decreases in perceived job satisfaction, which in turn influenced the decrease in the self-reported score of mental health. Specifically, the independent mediation analysis revealed that perceived work stress, perceived work–family conflict and perceived job satisfaction accounted for about 17.3, 22.4 and 16.5%, respectively, of the total effect of the association between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health, and the simultaneous mediation analysis revealed that the joint effect of all three mediators mediated about 36.2% of the total effect of the association between nonstandard work schedules and employees’ self-rated mental health, for work–family conflict, work stress and job satisfaction were correlated (Viegas and Henriques, 2021). Previous research has found that work satisfaction, work stress, and ability to control the work schedule were key contributing factors related to mental health via multiple linear regression analyses (Pitanupong et al., 2024), and we forward recognized that perceived work stress and job satisfaction mediated the association between work schedule and mental health. Our study is the first, to our knowledge, to explicitly test and confirm the mediating role of perceived work stress and job satisfaction in the association between work schedule and mental health.

On the other hand, work–family conflict mechanism has been proposed to account for the association between nonstandard work schedules and mental health in the USA adult samples (Cho, 2018), Australia employed parent samples (Zhao et al., 2021a), and Canada adult samples (Haines et al., 2008). Zhao et al.’s (2021a) study highlight the complex interplay between parents’ work schedules, work–family conflict and psychological distress. Cho’s (2018) study indicated a full mediation effect of work–family conflict, whereas Haines et al.’s (2008) study indicated a partial mediation effect of work–family conflict in the relationship between nonstandard work schedules and mental health. In our study, perceived work–family conflict was found to partially mediate the association between nonstandard work schedule and mental health, meanwhile, perceived work stress mechanism and perceived job satisfaction mechanism were also found in the multiple mediation model at one time, and these findings stand by Haines et al.’s (2008) study. Furthermore, Haines et al.’s (2008) research found that about 30% of the effect of shiftwork on depression was indirect through work–family conflict, and our independent mediation analysis indicated that about 22.4% of the effect of the association between nonstandard work schedule and self-rated mental health was indirect through perceived work–family conflict, but our simultaneous mediation analysis indicated that by adding perceived work stress and job satisfaction as mediators the proportion of the joint indirect effect raising up to about 36.2%. Moreover, our finding that relative to perceived work–family conflict, either perceived work stress or perceived job satisfaction mediates almost the same proportion of the relationship between nonstandard work schedules and employee’s self-rated mental health in the simultaneous mediation model is noteworthy, and we recommend that research examine the role of other psychosocial mechanisms for the association between nonstandard work schedules and mental health.

The results of this study provide for a more ‘precise’ understanding of the relationship between work schedule and mental health (Totterdell, 2005). We found that nonstandard work schedules cause increasing work stress and work–family conflict as well as decreasing job satisfaction, which can impact employees’ mental health. By including work–family conflict as a mediating variable, previous studies elucidated a social pathway between nonstandard work schedules and mental health besides biological pathway (Cho, 2018; Haines et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2021a). Possibly one of the theoretical implications of this study is that by adding perceived job satisfaction and work stress as mediating variables, we extend social pathway to psychosocial pathway. Furthermore, our findings reveal that perceived work stress, perceived job satisfaction, and perceived work–family conflict mediate almost the same proportion of the total effect between nonstandard work schedules and employee self-rated mental health. In addition, the majority of research on work schedules takes place in a few countries (Totterdell, 2005), there is a need for more evidence-based research from China. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first nationally representative study in China to investigate work schedules.

The results of the study may also provide practical implications for employers and policy makers to make policies and interventions on employees’ mental health and occupational health. In light of the effects of psychosocial mechanisms, the mediating effects of perceived work stress, work–family conflict and job satisfaction provide new insights to improve the mental health of employees with nonstandard work schedules, not only by improving sleep quality, but also by reducing both perceived work stress and work–family conflict, as well as raising perceived job satisfaction. Employees themselves should also be wary of nonstandard work schedules that could undermine their mental health not only through reduce sleep quality but also through increase work stress and work–family conflict as well as decrease job satisfaction.

There are various study limitations to note. First, although CGSS had included 12 waves so far, we were only able to use one wave of data given the availability of the work schedules measure only in the “quality of work topical module” added in the latest 2021 wave. As such, we cannot speak to causality between nonstandard work schedules and mental health. We are aware that mental health may affect job satisfaction, work-family balance and work stress, therefore, there is potential for a bidirectional relationship between the factors considered in our study. Given the availability of data, future research could employ a longitudinal analysis to better understand the causal relationship of the mediating roles of work stress, work–family conflict and job satisfaction between work schedule and mental health. Second, our nonstandard work schedules measure is mainly a simple dichotomous measure. Although we divided and considered different types of nonstandard work schedules in sensitivity analysis, and achieved some findings on the rotating shift and irregular schedule employees, small sample size for fixed night shift (about 1.29%) prohibited any meaningful analysis on fixed night shift employees. Also, we did not account for dose–response relationships, such as the frequency of working nonstandard schedules. We would like to encourage future researchers to replicate our study using alternative data and measurement sources. Third but not last, this study may be limited by potential self-report bias for the variables in this study were measured using self-report instruments, and the self-rated mental health, perceived work stress, perceived work–family conflict and perceived job satisfaction measure used in our study are single-item, and future research should consider replicating the current findings with more standardized, objective and multidimensional measure tools.

Limitations notwithstanding, our study provides a novel contribution to the body of literature on the relationship between nonstandard work schedules and mental health by considering the mediating roles of perceived work stress, work family conflict and job satisfaction. Our findings reveal that psychosocial factors, not only work–family conflict, but also perceived work stress and job satisfaction, may play mediating roles on the association between nonstandard work schedules and mental health. Future research should examine other potential psychosocial mechanisms underlying the association between work schedule and mental health to establish why work schedule variable is associated with mental health outcome, and it is important for the advancement of knowledge (Haines et al., 2008). For example, organizational participation, social contact, and solitary activities are some of the problems which the shift worker may encounter with greater frequency than the day worker (Dunham, 1977), and these factors may play roles with mental health. Another example is that workers with nonstandard work schedules may have unequal work assignments perception (Kida and Takemura, 2024), and the organizational justice may be another potential psychosocial mechanism underlying the association between nonstandard work schedules and mental health. There is still much to know, and more research is needed to enhance our understanding of the relationships between work schedule and mental health.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: http://www.cnsda.org/index.php?r=projects/view&id=65635422.

ZW: Writing – original draft. GZ: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the Major Program of National Social Science Fund of China (21&ZD044) and the National Natural Science Fund of China (71840010).

We thank the editor and reviewers for their helpful feedback. We thank the CGSS teams for making the data available for public use.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Al-Hammouri, M. M., and Rababah, J. A. (2023). Work family conflict, family work conflicts and work-related quality of life: the effect of rotating versus fixed shifts. J. Clin. Nurs. 32, 4887–4893. doi: 10.1111/jocn.16581

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Ambiel, B. S., Rapp, I., and Gruhler, J. S. (2024). Evening work and its relationship with couple time. J. Fam. Issues 45, 621–635. doi: 10.1007/s10834-023-09934-8

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Bagheri Hosseinabadi, M., Ebrahimi, M. H., Khanjani, N., Biganeh, J., Mohammadi, S., and Abdolahfard, M. (2019). The effects of amplitude and stability of circadian rhythm and occupational stress on burnout syndrome and job dissatisfaction among irregular shift working nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 28, 1868–1878. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14778

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Bian, Y. J., and Li, L. L. (2012). The Chinese general social survey (2003-8) sample designs and data evaluation. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 45, 70–97. doi: 10.2753/CSA2162-0555450104

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Bolino, M. C., Kelemen, T. K., and Matthews, S. H. (2021). Working 9-to-5? A review of research on nonstandard work schedules. J. Organ. Behav. 42, 188–211. doi: 10.1002/job.2440

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Brown, J. P., Martin, D., Nagaria, Z., Verceles, A. C., Jobe, S. L., and Wickwire, E. M. (2020). Mental health consequences of shift work: an updated review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 22, 1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-1131-z

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Castillo, B., Grogan-Kaylor, A. C., Gleeson, S., and Ma, J. (2020). Child externalizing behavior in context: associations of mother nonstandard work, parenting, and neighborhoods. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 116:105220. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105220

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, C. C., Ping, L. Y., Lan, Y. L., and Huang, C. Y. (2025). The impact of night shifts on the physical and mental health of psychiatric medical staff: the influence of occupational burnout. BMC Psychiatry 25:256. doi: 10.1186/s12888-025-06701-x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, B., Wang, L., Li, B., and Liu, W. (2022). Work stress, mental health, and employee performance. Front. Psychol. 13:1006580. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1006580

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Cheng, H., Liu, G., Yang, J., Wang, Q., and Yang, H. (2023). Shift work disorder, mental health and burnout among nurses: a cross-sectional study. Nurs. Open 10, 2611–2620. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1521

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chireh, B., Essien, S. K., Novik, N., and Ankrah, M. (2023). Long working hours, perceived work stress, and common mental health conditions among full-time Canadian working population: a national comparative study. J. Affect. Disord. 12:100508. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2023.100508

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Cho, Y. (2018). The effects of nonstandard work schedules on workers’ health: a mediating role of work-to-family conflict. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 27, 74–87. doi: 10.1111/ijsw.12269

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chong, Y. Y., Frey, E., Chien, W. T., Cheng, H. Y., and Gloster, A. T. (2023). The role of psychological flexibility in the relationships between burnout, job satisfaction, and mental health among nurses in combatting COVID-19: a two-region survey. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 55, 1068–1081. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12874

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Coelho, J., Lucas, G., Micoulaud Franchi, J. A., Tran, B., Yon, D. K., Taillard, J., et al. (2023). Sleep timing, workplace well-being and mental health in healthcare workers. Sleep Med. 111, 123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2023.09.013

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Das, M., and Palo, S. (2024). Shift work, sleep and well-being: a qualitative study on the experience of rotating shift workers. Manag. Labour Stud. 50, 148–165. doi: 10.1177/0258042×241286238

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 499–512. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Dong, Y., Wu, X., Dong, Y., Li, Y., and Qiu, K. (2024). Alterations of functional brain activity and connectivity in female nurses working on long-term shift. Nurs. Open 11:e2118. doi: 10.1002/nop2.2118

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Du, Y., Shahiri, H., and Wei, X. (2023). “I’m stressed!”: the work effect of process innovation on mental health. SSM Popul. Health 21:101347. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101347

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Dunham, R. B. (1977). Shift work: a review and theoretical analysis. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2, 624–634. doi: 10.5465/AMR.1977.4406742

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Fix, R. L., and Powell, Z. A. (2024). Policing stress, burnout, and mental health in a wake of rapidly changing policies. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 39, 370–382. doi: 10.1007/s11896-024-09671-0

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Frazier, C. (2023). Working around the clock: the association between shift work, sleep health, and depressive symptoms among midlife adults. Soc. Ment. Health 13, 97–110. doi: 10.1177/21568693231156452

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Gawlik, K. S., Melnyk, B. M., and Tan, A. (2025). Burnout and mental health in working parents: risk factors and practice implications. J. Pediatr. Health Care 39, 41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2024.07.014

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Golden, L. (2015). Irregular work scheduling and its consequences. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute.

Google Scholar

Greenhaus, J. H., and Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 10, 76–88. doi: 10.5465/amr.1985.4277352

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Haines, V. Y., Marchand, A., Rousseau, V., and Demers, A. (2008). The mediating role of work-to-family conflict in the relationship between shiftwork and depression. Work Stress. 22, 341–356. doi: 10.1080/02678370802564272

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Han, W. J. (2023). Work schedule patterns and health over thirty-years of working lives: NLSY79 cohort. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 42:18. doi: 10.1007/s11113-023-09768-0

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Han, T., Bi, J., and Yao, Y. (2024). Exploring the antecedents of airline employee job satisfaction and dissatisfaction through employee-generated data. J. Air Transp. Manag. 115:102545. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2024.102545

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Harris, R., Kavaliotis, E., Drummond, S. P. A., and Wolkow, A. P. (2024). Sleep, mental health and physical health in new shift workers transitioning to shift work: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 75:101927. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2024.101927

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Google Scholar

Hong, K. J. (2025). Effects of work demands and rewards of nurses on exhaustion and sleep disturbance: focusing on comparison with other shift workers. Nurs. Open 12:e70207. doi: 10.1002/nop2.70207

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

House, S., Wilmoth, M., and Stucky, C. (2022). Job satisfaction among nurses and physicians in an Army hospital: a content analysis. Nurs. Outlook 70, 601–615. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2022.03.012

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Huang, Y., Guo, H., Wang, S., Zhong, S., He, Y., Chen, H., et al. (2024). Relationship between work-family conflict and anxiety/depression among Chinese correctional officers: a moderated mediation model of burnout and resilience. BMC Public Health 24:17. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-17514-6

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Jeon, B. M., and Kim, S. H. (2022). Associations of extended work, higher workloads and emotional work demands with sleep disturbance among night-shift workers. BMC Public Health 22:2138. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14599-3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Jilili, M., Liu, L., and Yang, A. (2023). The impact of perceived discrimination, positive aspects of caregiving on depression among caregivers: mediating effect of job satisfaction. Curr. Psychol. 42, 194–202. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01397-0

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Jung, S., Lee, S.-Y., and Lee, W. (2022). The effect of change of working schedule on health behaviors: evidence from the Korea labor and income panel study (2005–2019). J. Clin. Med. 11:1725. doi: 10.3390/jcm11061725

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kachi, Y., Abe, A., Eguchi, H., Inoue, A., and Tsutsumi, A. (2021). Mothers’ nonstandard work schedules and adolescent obesity: a population-based cross-sectional study in the Tokyo metropolitan area. BMC Public Health 21:237. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10279-w

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Karasek, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 24, 285–308. doi: 10.2307/2392498

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kerr, M. L., Botto, I., Gonzalez, E., and Aronson, S. (2025). Parental burnout and mental health across COVID-19 parenting circumstances: a person-centered approach. J. Marriage Fam., 1–20. doi: 10.1111/jomf.13093 [Epub ahead of print].

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kida, R., and Takemura, Y. (2024). Relationship between shift assignments, organizational justice, and turnover intention: a cross-sectional survey of Japanese shift-work nurses in hospitals. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 21:e12570. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12570

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kim, S. E., Lee, H. E., and Koo, J. W. (2023). Impact of reduced night work on shift workers’ sleep using difference-in-difference estimation. J. Occup. Health 65:e12400. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12400

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kim, J., Lee, E., Kwon, H., Lee, S., and Choi, H. (2024). Effects of work environments on satisfaction of nurses working for integrated care system in South Korea: a multisite cross-sectional investigation. BMC Nurs. 23:459. doi: 10.1186/s12912-024-02075-9

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kim, M., Li, N., Hu, M., and Jung, N. (2025). Measurement matters: prevalence and consequence of parental nonstandard work schedules. Soc. Indic. Res. doi: 10.1007/s11205-025-03600-2 [Epub ahead of print].

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kim, K. Y., Messersmith, J. G., Pieper, J. R., Baik, K., and Fu, S. Q. (2023). High performance work systems and employee mental health: the roles of psychological empowerment, work role overload, and organizational identification. Hum. Resour. Manag. 62, 791–810. doi: 10.1002/hrm.22160

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Koutsimani, P., Montgomery, A., and Georganta, K. (2019). The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 10:284. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00284

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Lambert, A., Segu, M., and Tiwari, C. (2023). Working hours and fertility: the impact of nonstandard work schedules on childbearing in France. J. Fam. Issues 45, 447–470. doi: 10.1177/0192513X221150975

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, H. Y., Kim, M. S., Kim, O., Lee, I.-H., and Kim, H.-K. (2016). Association between shift work and severity of depressive symptoms among female nurses: the Korea Nurses’ health study. J. Nurs. Manag. 24, 192–200. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12298

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, J., Lim, J. E., Cho, S. H., Won, E., Jeong, H. G., Lee, M. S., et al. (2022). Association between work-family conflict and depressive symptoms in female workers: an exploration of potential moderators. J. Psychiatr. Res. 151, 113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.04.018

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, J., Johnson, S. E., Han, W. J., Andrews, S., Kendall, G., Strazdins, L., et al. (2014). Parents’ nonstandard work schedules and child well-being: a critical review of the literature. J. Prim. Prev. 35, 53–73. doi: 10.1007/s10935-013-0318-z

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Matti, N., Mauczok, C., Eder, J., Wekenborg, M. K., Penz, M., Walther, A., et al. (2024). Work-related stress and sleep quality—the mediating role of rumination: a longitudinal analysis. Somnologie. doi: 10.1007/s11818-024-00481-4 [Epub ahead of print].

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

McNamara, K. A., and Robbins, W. A. (2023). Shift work and sleep disturbance in the oil industry. Workplace Health Saf. 71, 118–129. doi: 10.1177/21650799221139990

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Monahan, C., Zhang, Y., and Levy, S. R. (2023). COVID-19 and K-12 teachers: associations between mental health, job satisfaction, perceived support, and experiences of ageism and sexism. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 23, 517–536. doi: 10.1111/asap.12358

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Niedhammer, I., Bertrais, S., and Witt, K. (2021). Psychosocial work exposures and health outcomes: a meta-review of 72 literature reviews with meta-analysis. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 47, 489–508. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3968

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Niedhammer, I., Coutrot, T., Geoffroy-Perez, B., and Chastang, J. F. (2022). Shift and night work and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: prospective results from the STRESSJEM study. J. Biol. Rhythm. 37, 249–259. doi: 10.1177/07487304221092103

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Ong, W. J., and Johnson, M. D. (2023). Toward a configural theory of job demands and resources. Acad. Manag. J. 66, 195–221. doi: 10.5465/amj.2020.0493

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Pitanupong, J., Anantapong, K., and Aunjitsakul, W. (2024). Depression among psychiatrists and psychiatry trainees and its associated factors regarding work, social support, and loneliness. BMC Psychiatry 24:97. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-05569-7

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Romo, L., Zerhouni, O., Nann, S., Rebuffe, E., Tessier, S., Touzé, C., et al. (2025). Assessment of burnout in the general population of France: comparing the Maslach burnout inventory and the Copenhagen burnout inventory. Ment. Health Sci. 3:e97. doi: 10.1002/mhs2.97

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Roskams, M., McNeely, E., Weziak-Bialowolska, D., and Bialowolski, P. (2021). “Job demands-resources model: its applicability to the workplace environment and human flourishing” in A handbook of theories on designing alignment between people and the office environment. eds. R. Appel-Meulenbroek and V. Danivska (London, LON: Routledge), 27–38.

Google Scholar

Royston, P. (2004). Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata J. 4, 227–241. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0400400301

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Sateia, M. J. (2014). International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest 146, 1387–1394. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0970

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Sierpińska, L. E., and Ptasińska, E. (2023). Evaluation of work conditions of nurses employed in a shift system in hospital wards during the COVID-19 pandemic. Work 75, 401–412. doi: 10.3233/WOR-220275

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Smith, J. M., Raina, S., and Crosby, D. (2023). “Parental nonstandard work schedules and family well-being” in Encyclopedia of child and adolescent health. ed. B. Halpern-Felsher, vol. 2 (Elsevier: Academic Press, NY), 699–708.

Google Scholar

Son, J., and Lee, S. (2021). Effects of work stress, sleep, and shift work on suicidal ideation among female workers in an electronics company. Am. J. Ind. Med. 64, 519–527. doi: 10.1002/ajim.23243

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Song, K., Lee, M. A., and Kim, J. (2024). Double jeopardy: exploring the moderating effect of educational mismatch in the relationship between work-family conflict and depressive symptoms among Korean working women. Soc. Sci. Med. 340:116501. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116501

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar